March Issue 2001

Polish Paintings In The Sztyber Collection at Art Gallery Unlimited*, Charlotte, NC

by Jurek Polanski, Visual Arts Correspondent for www.ArtScope.net

Polish Paintings in the Sztyber Collection will be on display at the Art Gallery Unlimited in Charlotte, NC, Mar. 1 through 31. The artists presented in exhibition are: Grzegorz Stec, Jan Lebenstein, Kiejstut Bereznicki, Krystyna Brzechwa, Antoni Kowalski, Henryk Musialowicz, Kazimierz Ostrowski, Janusz Przybylski, Jacek Wojciechowski, Franciszek Starowieyski, Andrzej Umiastowski, Jacek Palucha and Daniel Sztyber.

Public and national museums owe much of their treasures to private collections. Many began as private collections - royal, aristocratic, or of connoisseurs - and subsequently become public. Many more have grown and diversified primarily through private benefactors. An astute individual recognizes objects of value, collects and researches them, and others follow suit, drawing upon his example and expertise. One need only recall such examples as Joseph H. Hirshhorn, Henry Clay Frick, or Daniel J. Terra, whose collection became its own independent museum. Other institutions consult private collectors to guide their own acquisitions: collectors specialize and surpass hard-tasked generalists; they exercise uncompromising judgement, and often, in the case of art, they form supportive liaisons with living artists. Private collections, directed and coherent, always exert a strong fascination. This explains why the exhibition from Chris Sztyber's collection of Contemporary Polish Art is an important showing. The Sztyber collection is an actively growing undertaking, and it may be approaching the most comprehensive and methodically selected representation of modern Polish paintings in the United States. The quality of the work is very high, and its areas of interest encompass not only accomplished and renowned artists, but exceptional emerging talents.

Grzegorz Stec is prominent among the artists selected from the Sztyber collection, and he is here represented by three canvases; Sand (Piasek) (1997, oil on canvas, 39 1/2" x 39 1/2"); Studio (Pracownia) (1993, oil on canvas, 26" x 36 1/2"); and Tower of Babel (Wieza Babel) (1977, oil on canvas, 59" x 79"). Stec, born in Cracow, Poland, in 1955 graduated from the Faculty of Graphic Arts in the Academy of the Arts in Cracow in 1981. Stec's paintings display a striking interplay of vivid color with turbulent brushwork. His paintings counterpoise what seems a fluid working of paint with a disciplined feel for final composition. At first glance, his allegoric fantasies, so reminiscent of a modern Hieronymous Bosch, seem abstractions. But the artist, in an interview with Ewa Krason has stated: "There is no abstract painting. As we get to know the world, nature and all its structures, we discover that all the forms we try to dub abstract already exist. We are made of the world and we cannot think with anything else but the world." A viewer, drawn to the work, upon closer inspection discovers and explores the core of actuality in each painting. Stec, who paints constantly, begins with impulse, a worldly response, and builds creative tension until a painting brings itself to fruition. In his virtuosity, expression and interpretation are unhindered by difficulty of medium or technique.

In that same conversation with Krason, Stec observed: "Technique is very important to me. Fully mastered, it permits freedom. Sand exemplifies Stec's art. At a reasonable viewing distance, it conjures a sense of super-realism. Upon closer examination, the detail dissolves into loose, impressionistic brushwork. The mountains of "Sand," at close sight, seem cob-webbed cinder, ancient and unregarded. The human 'gravel' which constitutes the clashing armies dwarfed below and the fore, upon closer inspection, dissolve into flecks and specks of color. Their most eye-catching feature are their pennants of war, and their pikes and staves aligned toward the central clash of arms. In all, Sand would seem a commentary, subtle and entirely in image, upon the vanity of human strife, obscured in mists, unmindful of the enduring majesty towering about it: Man, no matter how heroic or self-gloried, here seems an ant, unremarkable and all too soon prepared for a return to dust again.

Grzegorz Stec told art critic, Ewa Krason; "I believe that the deeper one enters oneself, the more learns about oneself, the better the chance for genuine and not concocted originality. On the other hand, when I hold but a small leaf in my hand, I become humble." Tower of Babel would seem to follow a similar theme. Here, the borders of the canvas crop what seems an even more immense domed tower, honeycombed in tiers of eremite cells or coralline rows of windows. The tower evokes a sense of great, but unreal industry, mindlessly applied and futilely repeated. Studio presents a space far more confined, an architecture as much mental as visual. A strong, sun-like focus of light above the painting's indistinct forms adds to the phantasmagoric effect - artist's studio as a Dante's Purgatorio or a labyrinth by Piranesi. The working style in paintings such as these displays an opulence of palette worthy of Gustave Moreau.

Jan Lebenstein was born in 1930 and survived the Nazi occupation of Poland. He received his diploma from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Poland in the mid-1950s. Lebestein died in 1999 after years of ill health. Much of his painting emerged as cycles of work - Monstrous Animals (Potworne Zwierzeta), Intimate Notebook (Notatnik Intymny), and the like. In the 1960s, the substance of his work shifted from mystical idols to subdued, monochromatic paintings, but a synthesis of mythology and modernity pervades much of his art. His mature technique often reinforces and highlights flat surface contours with a thickly applied impasto to produce paintings approaching bas-relief. This latter low sculpting of raised, often globular paint ridge and mass in many works contributes to a distinctive, pebbly texture of the painting's surface. Lebenstein's palette favors a scheme of subtle earth hues: ochres, umbers, sepias - and, where reds, violets or blues do enter in, they emerge in subdued, twilight tones, gently desaturated.

Axial Figurine #124 (Figura Osiowa #124) (1961), in its irregular, imperfect axial symmetry, recalls a Rorschach blot, one resulting as if from an immense and monstrous insect crushed into the panel. Elements within the composition blend natural forms and textures which recall both arthropod and devil-fish: a procrustean unity of living, primitive morphologies. Patagonia (1964, oil on canvas) seems a well-preserved fossil vertebrate, vaguely mammal-like, or reptilian, which has been needled into view from within a slab of rock. Lebenstein ranged widely for inspiration and the title is suggestive. In Patagonia, Lebenstein evokes both fossil relic, and at the same time, memories of the dragons and manticores which the mythic sense of man fashioned from them. Demode (1965). a wry title seems closer to a partially articulated mummy of Patagonian flesh and bones, although in the converged masses of the matrix there are as well suggestions of severed feet and similar portions of the human torso. Lebenstein's paintings, surpassing their meticulous working of media and detail, provoke overtones and obligatos beyond immediate theme. Ballon Baba (1967), despite the female's large rump, displays ribs protrusive in relief: here is revealed a plentitude of flesh, branded with a prefigurement of mortal flesh's ultimate destiny.

In 1959, Lebenstein received the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris. His work is represented in the New York Museum of Modern Art by 27 items; in the Smithsonian Institution Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. by thirteen pieces; in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and in numerous similar institutions.

Kiejstut Bereznicki

Kiejstut Bereznicki

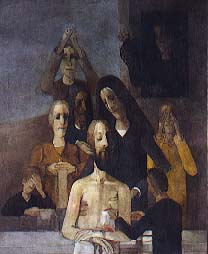

Kiejstut Bereznicki is represented by three paintings, all oils on canvas: Washing (Obmywanie) (1992); Family Scene in Blue (Scena Rodzinna w Blekitach) (1964); and Kitchen Still Life (Martwa Natura Kuchenna) (1992). Bereznicki is a particularly interesting painter. His works in this showing reveal an somewhat Dutch Gothic sense of decorum: a quiet, if not stoic, religious sensibility akin to Rogier van der Weyden or Hugo van der Goes. But Kiejstut Bereznicki transforms that meditation to a far more contemporary and yet austere classical expression. His figures are not the high-born and gentile personages frequent in past masters, but simple, working-class people. The artist's personal idiom here invests a religious iconology with a renewed and authentic expression; they are consonant with our present-day awareness of their source and inspiration. The Jesus of the Gospels was born in a manger, and for much of his life worked as a carpenter. In this artist's choice to finely and delicately distill his portraiture, rather than employ a rich, but illusory naturalism, attention is focused upon each painting's content, not upon the virtuosity of its interpreter. Bereznicki, in exposition, seems in sympathy with such an American artist as Grant Wood and the latter's American Gothic (1930), albeit without the American's half admiring, half touch of irony toward his subject. His paintings in this exhibition reveal an authenticity and serious consideration which befits a society that suffered two catastrophic world wars, as well as a subsequent and failed 'dialectical materialism'.

One first impression upon viewing Bereznicki's paintings in this showing is that they arise from what D.H. Lawrence named "the real stuff of tragedy the primitive, primal earth, where instinctive life heaves up.... (and) the deep, black, source from whence all these little contents of life are drawn." (Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays, by Ed Bruce Steele, Cambridge, 1985). In these paintings, each person seems wrapped in a private grief, even as they wrap the body in its death cloth. Bereznicki's paintings evoke the dignity of a great revelation, clothed in low circumstance, yet one which reveals itself in the intimate decorum of common faces and simplest objects, This recalls the insight of D.H. Lawrence's short story "Odour of Chrysanthemums", the moment when the corpse of the dead miner, smothered by a roof collapse, is brought home to his mother and his family to be washed and prepared for burial:

"Her soul was torn from her body and stood apart. She looked at his naked body and was ashamed, as if she had denied it. After all, it was itself It seemed awful to her. She looked at his face, and she turned her face to the wall. For his look was other than hers, his way was not her way. She had denied him what he was - she saw it now. She had refused him as himself - And this had been her life, and his life. - She was grateful to death, which restored the truth. And she knew she was not dead."

And, in the same prose, Lawrence might have well been referring to Bereznicki's Family Scene in Blue:

"It was hard work to cloth him. He was heavy and inert. A terrible dread gripped her all the while: that he could be so heavy and utterly inert, unresponsive, apart. The horror of the distance between them was almost too much for her - it was so infinite a gap she must look across."

A similar reserve is revealed in the titles of Bereznicki's paintings. A viewer is called upon to discern and recognize the art's frame of reference; to see it is actuality, not as idealized, stylized., which today is accounted dismissible (because complacently held as rote cultural baggage). Here is an earthly reality, accessible, yet held at a distance for considered scrutiny. A viewer is prompted to seek for himself the very unmundane, the spiritual intent contained therein. Bereznicki's approach presumes no uncritical sympathies, coerces no assent without consideration of his subject. This strategy is furthered by the artist's inclusion of sparse but telling detail and formal gesture which calls for viewer interpretation. In centuries of Christian metaphor, the soul has been compared to a bird caged within the body, and in "Washing" such a cage is presented by the woman framed in a window at right. In Family Scene in Blue one notes the carpenter's hammer beside the washing bowl. They serve as pregnant emblems for the initiated. Bereznicki writes as well as paints, and his poems and drawings were featured in the arts monthly, Arkusz (paper sheet) (Poznan: May 1999).

Kazimierz Ostrowski's Shipyard (Stocznia) (1970; oil on canvas) analyzes its named subject in terms of Cubist paradigms, and its dominant color scheme rests with blues, greys and white. One discerns affinities with Kasimir Malevich, and Russian pre-Revolutionary Constructivism, but a salient aspect of this painting is its overall integration of component foci, and a dynamic, sustained tension between horizontal and vertical stress. Shipyard displays a near decorative, seemingly muralistic formalism of geometry which, in its clean line and sharply defined tesselations, abstracts its subject and yet gratifies.

Franciszek Starowieyski's Untitled (1981: gouache on paper) poses an enigmatic visual equation. The focus of the painting's upper half is a female form, seemingly splayed for mount, but the left leg is itself an auxiliary figure, devoid of limbs, with a tubular umbilicus emerging from one eye socket. A viewer notes the heads of mechanical screws which evidently affix the anthropomorphic thighs to the image ground. A larval, insect-like creature occupies the lower half of this work, and it is flat on its back, much in a posture of death, or perhaps dormancy. This latter image recalls Franz Kafka's famous story, "Metamorphosis," although here it lies at the foot of a female form, either as offering, vanquished supplicant, or iconic harbinger of uncanny future. Starowieyski's fusion of female torso, embryonic form, and mechanical fasteners, in its vocabulary of image element, recalls the chimeras of animate and inanimate found in the art of Hieronymus Bosch, and even more, the dark work of contemporary German artist, H.R. Giger. But Starowieyski's use of visual motif is more iconic than the latter's: there is less a fascination with the image for shock of itself, and a greater attention to the significance of their specific associations. Here, one discovers an ambiguity in the female's situation, for her pose might as well be one of birth-giver as that of mounted specimen, Untitled certainly appears as a metaphor, a parable which each viewer is invited to articulate for himself It is a disturbing provocateur of human anxieties, and nourished by man's own Faustian scientific ingenuity and social accommodations. Despite the somber beauties of Starowieyski's technique and execution, Untitled conveys the unease of a Franz Kafka or Aldous Huxley...

"...the real horror of the situation in an industrial or administrative Panopticon is not that human beings are transformed into machines (if they could so be transformed, they would be perfectly happy in their persons); no, the horror consists precisely in the fact that they are not machines, but freedom-loving animals, far-ranging minds, and God-like spirits, who find themselves subordinated to machines and constrained to live within the issueless tunnel of an arbitrary and inhuman system."

Franciszek Starowieyski

Franciszek Starowieyski

Franciszek Starowieyski was born in 1930. He studied at The Croacow Academy of Fine Arts and later graduated from Warsaw Academy. The artist himself has noted that, well before studying in Warsaw, "What fascinated me then was satire of imaginary world of terrifying capitalists, top hat-clad bloodsuckers. . .I was fascinated by the world of evil and darkness, by Daumier and Borowczyk (Polish filmmaker and writer Walerian Borowczyk). . . Although primarily a fine artist, Starowieyski is noted for his active collaboration in theater (he played David in the 1982 Paris production of Andrzej Wajda's Danton), as well as for his contributions in poster art and commercial graphics. An artist who often provoked authorities under Poland's post-WWII Socialist regime. Starowieyski has brought discipline and a sharp edge from applied graphics into his paintings. The artist may, as an individual, be a restless creator, but his work is incisive, striking and highly individual.

Antoni Kowalski

Antoni Kowalski

A vocabulary of surreal biological elements, biomorphism, need not result in wry and dark prophesy, Antoni Kowalski employs a biomorphic idiom, one which creates metaphors between animate and inanimate, but in Kowalski's art it blossoms into fantasy and wondrous effect. In Red Prayer, the central focus of the painting presents what might be inspired by insect leg, saprophytic stem sheath or stems with peeling red skins. In some works, image elements recall arthropod cuticle, the familiar 'shell' of lobster and locust. At other times, the imaginary seems more like cloths of varying pattern and texture. Such a basic formulation establishes a vocabulary which is characteristic for the entire painting, and in the satellite images which ring the central focus of Red Prayer, these image characteristics, in each isolated and subordinate miniature, suggestively construct visions of monk, mushroom, poisonous bamboo, where evident natural features conspires to imitate man-made artifact.

In Blue Prayer, image characteristics resemble tarpaulins or tissues. Intuitive form rings true here as in much of Kowalski's art. A viewer's specific reading must decide whether a particular element resolves as celery stems cross-cut or whether they are fantastical lily-pads. And are the strange constructions which arise from the waters but wooden pilings concealed by cloths, or an aberrant form of biological emergence. Kowalski was born in 1957. He is thus the heir to both Surrealism, Magic Realism, and free-form experimentation in visual execution. The artist has noted an obligation towards art and yet a need to search new areas, although he rejects much of the superficiality of conventional 'new media'. He develops earlier repertoires of expression, but always with an intent to bring something into view is distinct, novel, and yet communicative to fellow men. Kowalski has called his major concern the states of mind on a transcendental plane and the "third eye of the mind". Antoni Kowalski studied at the Department of Graphic Art, Katowice, and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow.

Jacek Wojciechowski is a Polish artist whose work is difficult to categorize, but which delights in its detail and associations. Wojciechowski is another artist who seems impatient with reality, and yet who ranges for inspiration through time, cultures and the bric-a-bracage of the dreaming mind. He is represented in this exhibition by two works: "on a flying carpet, or maybe balloon, one dark september night they brought me a wife (latajacym dywanem, a moze balonem, ciemna wrzesniowa noca przwiezli mi zone)" (1994, oil on canvas) and A day before Adam was born (Dzien przed narodzeniem Adama) (1991: oil on canvas). Many of Jacek Wojciechowski's canvases operate in Euclidian space, flat planes; but the events, or tableaux which therein transpire - the subliminal relationships between object forms - belong to no world known, at least in a waking state.

The paintings of Henryk Musialowicz are somber, shadowy, and there is the indefinable air of midnight basilica or darkened sacristy about them. If they evoke sacramental icons, then in content, and the artist's intents and inspirations, they serve a faith in that part of man which, as St. Augustine one declared, is in this world, but not of it. Musialowicz himself, although aware of such comparisons, demurs and ranges beyond definable traditions, In a 1995 exhibition Eternal Energy, he asserted: "I am haunted by this charism of pain and suffering. I know that more than one I shall see Our Lady of Sorrow's face in that of one of my fellows. I am not interested in 'icon art because its very orthodox and limited form does not open itself to the problems of our times, but the grief in her eyes is the sadness of the whole world."

Born in 1914, Musialowicz started out as a realistic painter. Beginning in 1956, he initiated an eight year laboratory of new forms which led him to a repertoire characterized by understatement - a figurative reduction - as well as the invigoration of a new and personal symbolism. A large portion of his art has been conceived as cycles. And many of this artist's paintings exploit subtle, glazed, layered and enamel-like effect, often highlighted by gold and silver. Musialowicz's art may begin its birth with a figurative armature, but for the artist, collaborative associations, echoing of form and past conventions, visual similes, all gather to produce a fixed and enduring center of emotion and regard. Musialowicz fashions an art which finds, as in Animalistic Landscape (1962/64: mixed media), the common, shared archetype in paleolithic cave paintings, Celto-Iberian and Minoanbull rituals, and Middle-Eastern or Biblical art. All human cultures acquire a language for art, each with a peculiar idiom, but that artistic specific, although minted and learned, still builds upon a common human perception and experience. The artist's prime concern is: "A real picture does not and cannot exist in nature because a work of art is rather a symbol than a straightforward statement." Musialowicz furthermore places a collaborative importance on his framing: he, together with his wife, fashions frames as an integral part of a painting's totality. Musialowicz experiments widely with surface, both in texture and reflectivity. His Animalistic Landscape reveals two ox-like forms to the foreground of a reduced, abstracted horizon and ground. An upper glaze of silver is effaced in parts of the image to reveal an underlying gold infill. In the right-most form, this gold surface is much of the animal's color. The surface throughout the painting is scored, frequently in small patches of incised ribbing. Examining closely Musialowicz's "From the Series. Family" (1981: mixed media), one discerns the almost feminine figure, center at right, as a filigreed and softened form; at the left is a brighter, glowing, figured prominence in form. In the lower canvas, three forms, indistinct but for their central shaft of vertical gold, emerge as subordinates, satellites.. offspring. But these offspring further resemble candle forms; light renewed.

Janusz Przybylski

Janusz Przybylski

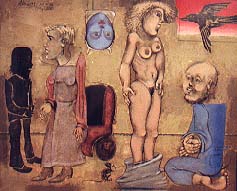

Janusz Przybylski is represented by three paintings in this showing. In Atelier 06.30.1996 (1996: gouache) a viewer's attention focuses on the central female model and the bird, framed by red color, at the upper right corner. A wheel chair at left focus stands below a horned facial mask. The general sense of this artist's studio scene is one of homage, perhaps even self-abasement before the taut, almost muscular vitality of the female model - the surrounding figures offer a monastic air. Atelier 12.08.1996 (1996: gouache) takes as central figures horse and bare-back rider, which are flanked by two woman at right, and a male, as well as disassociated head, at left.

Janusz Przybylski applies a Picassso-esque sense of distorted form: multiple perspectives are coalesced upon each image element. These works recall Picasso's classical style of the interwar era. In them, the artist freely arrays image elements in visual ensemlage, all painted on a conspicuously flat surface, with a deliberate effort to defeat dimensional illusionism. Because the components seemed gathered from disparate sources and reinterpreted into a unified canvas each calls attention to its individualized presence: a viewer is prompted to query its function - its purpose there. The lack of any interpretive clues for the evident narrative situation, other than ambient presence in an artist's studio, focuses consideration upon a general, familiar pattern of interaction, It evokes a mime of human rituals, unspecified and open for the viewer. Polish art critic Lechoslaw Lanienski called Przybylski's art "a marvelous saga on the imperfections of human fate, on sin and salvation, on hypocrisy and deceit; condemning conceit and stupidity, encouraging love and tolerance, teaching how to optimistically open ourselves to the future." That may represent an intent. Or an effect. But the possibilities are all-present in the art And worth the gallery visitor's considered attention.

Krystyna Brzechwa

Krystyna Brzechwa

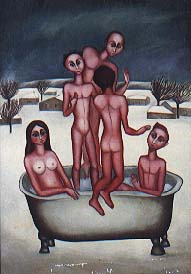

The artists first discovered it; exploited it; became aware. Decades later biologists confirmed that one of the reasons humans respond to large eyes and disproportionate heads, was that they characterize infants. The traits called forth protectiveness, affection. And when they are met with, joined to serious matters of the world, a very adult world, one is struck with dissonance, forced to reconsider the whole affair: a human comedy. The work by Krystyna Brzechwa is fanciful and illustrative, and she is represented in the collection by Bathtub (1979: oil on canvas), and Red Ballet (1974: oil on canvas). Imps,waifs, nudes naif, Brzechwa's visual vocabulary is often poignant in its recourse to the large eyes of the figures, their graceful, balanced postures and implied movement.

Andrzej Umiastowski

Andrzej Umiastowski

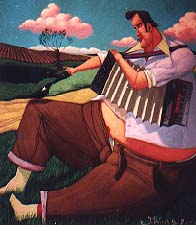

Andrzej Umiastowski's two oils on canvas: Troika (Trojka) (1998), and Wedding (Slub) (1997), tend to approach the life and foibles of the bourgeois with a knowing, and gentle amusement. In this sensibility, he seems akin to Max Beerbohm, although for the artist, contentment, complacency, or a Walter Mitty pleasure at mundane life is concomitant with an expanding waistline. Perhaps, in honesty, it is. Both Wedding and Troika are representative of Umiastowski subjects; private moments, private lives often lost in the small joys of a moment: portraits of the at times incongruously contented.

*

*

Jacek Palucha

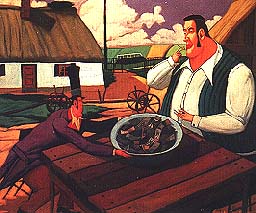

Jacek Palucha is represented by Bird's Friend (Przyjaciel Ptaka) and The Profound Care for the Well-being of a Simple Man (Diabelska Troska o Dobrobyt Prostego Czlowieka) both oils on canvas painted 2000. Palucha paints in a crisp, clean manner, and his paintings reveal a dry, covert wit. In composition, his art recalls some of Thomas Hart Benton's expressive turn of forms in display. In the Profound Care for the Well-being of a Simple Man, and somewhat Paul Bunyan-like farmhand is showered with offerings by an obviously well-heeled member of society. Such, however, are not mankind's realities, but his daydreams: 'All for the best, and it couldn't be better, in this best of all possible worlds.'

The paintings in the Sztyber collection, despite their great variety, have an edge, content. That may arise from the judgement and taste of the collector. But, having seen a large survey of art from Central Europe, a certain distinctiveness emerges. A country such as Poland, part of the European history, remained aware of the course of art elsewhere, even when it was not cultivated or encouraged. Art there has always been an essential act of life, and modern history has offered no leisure or idle self-complacency to eviscerate it. One reads art writing from the US and Western Europe...to frivolously speculate the fine points of arcana about art - 'Deconstructionism', 'Dantoism', and the ilk - contrasts with art arising from rich ground, art which has been hardened and which has prevailed with greater resolve in the face of adversity. Post-WWII regimes which sought to totalitarianize art ended with pruning and invigorating it. In this art there is a content, content with significance. Perhaps the only single trait which fully links these diverse artists is a conviction that art is a vital activity, one which passes from artist to viewer; an activity which,whatever its intents and purposes, nonetheless is infused with import and consequence, open-ended perhaps, even contrary to itself, but vital and generative.

For further information check our NC Commercial Gallery listings or call *Daniel Sztyber at MicroCosm Art Gallery at 704/618-6568.

Mailing Address: Carolina Arts, P.O. Drawer

427, Bonneau, SC 29431

Telephone, Answering Machine and FAX: 843/825-3408

E-Mail: carolinart@aol.com

Subscriptions are available for $18 a year.

Carolina Arts

is published monthly by Shoestring

Publishing Company, a subsidiary of PSMG, Inc.

Copyright© 2001 by PSMG, Inc., which published Charleston

Arts from July 1987 - Dec. 1994 and South Carolina Arts

from Jan. 1995 - Dec. 1996. It also publishes Carolina Arts

Online, Copyright© 2001 by PSMG, Inc. All rights reserved

by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. Reproduction or use

without written permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina

Arts is available throughout North & South Carolina.