September Issue 2002

Furman University in Greenville, SC, Martha Simkins Traveling Retrospective Exhibition

American painter Martha Simkins (1866-1969) was a noteworthy, recognized artist in Dallas, TX, in the first half of the twentieth century. This is the first retrospective exhibition to bring her work to the public's attention and to champion her impressive accomplishments and influence during a career that spanned more than eighty years. The traveling exhibition consists of more than 50 works and is comprised of portraits, figural images, still lifes and landscapes. The exhibition entitled Martha Simkins Rediscovered and its national tour is organized and curated by Robert A. Horn of New York City, in association with Martha Simkins, Inc., and will trace the career of one of the Southwest's most overlooked regional artists. The exhibition has been generously sponsored and supported by Roger E. Saunders and Mr. and Mrs. Jim Eitelman. The exhibition will open at the Thompson Gallery, Roe Art Building at Furman University in Greenville, SC, from Sept. 16 - Oct. 26, 2002, and will be seen in several museums across the country in 2002 and 2003. The exhibition at Furman is made possible by underwriting by Jim Simkins, The Simkins Company, Greenville, SC.

Martha Simkins Rediscovered is accompanied by a fully illustrated color catalogue and contains scholarly essays by Dr. Valerie Leeds and Dr. Melina Kervandjian.

Cape Cod Picnic

Cape Cod Picnic

Born in Florida following the Civil War, and raised in Texas, Martha Simkins divided her time as an adult between New York City, where she maintained a studio for several years, and her home city of Dallas, TX. In Dallas, Simkins was recognized as an accomplished portrait painter and received regular commissions from local citizens, though she also painted many non-commercial portraits, including self-portraits, figural images, still lifes and a few landscapes of New England and the West Coast. Simkins came from a prestigious Southern family and given her family history and background, it was, to some degree, unusual and rather bold for this young, unmarried woman to have ventured - albeit with her mother and three siblings - to New York City in the early 1890's to pursue an art education and a career as a professional artist. But, what perhaps in most unusual, is that her career path seems unexpectedly to have placed her first on the national scene rather than the local or regional stage in TX. After spending her formative years in New York, studying with such influential and highly regarded teachers such as William Merritt Chase, Frank DuMond, H. Siddons Mowbray, Kenyon Cox, and Robert Henri at the Art Students League, Simkins exhibited at such well-known national and international venues as the National Academy of Design, New York, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, the Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, the Southern States Arts League, and the Paris Salon. She befriended many artists while in New York and became affiliated with leading art organizations, among them, Pen and Brush Club (1918), a multi-disciplinary cultural club for women, that had been founded in 1893, The National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, and several organizations in Dallas. The Art Students League was of primary importance to her future career and according to current records, she initially studied there 1892-1899 and returned to enroll in classes for many years thereafter, and even as late as 1961 when she again roomed at the YWCA when she was 95 years old. She became friends with fellow woman artists such as Anna Fisher, Isabel Cohen, and Gladys Wiles, and visited Europe on at least several occasions during the 1920's. It also appears that she spent summers at the summer school of the Art Students League at Woodstock, New York, and also may have studied with Chase at Shinnecock.

Portrait of Mrs. Asher D. Cohen

Portrait of Mrs. Asher D. Cohen

In Jan. 1926, her work was exhibited at the Ainslie Galleries in New York and in May 1927 she sailed to France and exhibited at the Paris Salon. As discussed above, she divided her time between New York, Dallas and Woodstock until she returned home to Dallas on a permanent basis in 1934. In 1927, Simkins entered the painting Portrait of Mrs. C (a/k/a "Mrs. Asher D. Cohen") (Collection Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association, Charleston, SC) in the Southern States Art League annual exhibition. A portrait of the mother of her friend and fellow artist, Isabel Cohen, seems to be, from current research, Simkin's most important work. It is unclear whether it was a commissions piece or a subject she chose to do on her own and there is also a suggestion that it was presented as a gift from the artist. This penetrating work depicts the sitter up close and engaged with the viewer. Typical of Simkins' forthright technique, it is uncompromising in its realism - the subject is wearing a pince-nez and a mourning veil - and is executed in a sensitive painterly manner. This work had previously been shown at the 1919 National Academy of Design annual exhibition, at the Corcoran Gallery in 1923, at the Albright Art Gallery (now known as Albright-Knox Art Gallery) in Buffalo in 1924, the 1926 Carnegie International Exhibition, and at Ainslie Galleries in New York in 1926.

The Southern States Art League Exhibition held at the Gibbes was the prestigious platform for which Simkins received the Carolina Art Association Prize and the portrait was included in the Southern Exposition held at the Grand Central Palace, New York, May 11-23, 1929. This portrait was also presented in a number of Dallas group exhibitions in the 1920's and was repeatedly singled out and featured in the local press. Martha Simkins was lauded as "one of America's leading women portrait painters" and it appears from current scholarship that it is the only work that she is known to have submitted to annual major exhibitions outside of Texas. This aspect of Simkins' life, along with several other questions, remain for future scholarship. Though it is not possible to say with certainty why Simkins did not get much wider notice, according to the essay by Dr. Valerie Leeds, it is the author's opinion that her relative obscurity is principally attributable in large part to her return to Dallas, where she remained removed from the artistic mainstream of major art capitals, and to the fact that she ceased exhibiting in major annual exhibitions considered to be essential in the art world to attaining an enduring reputation. Therefore, according to Leeds, "Ultimately, however, she remained an artist of regional reputation."

Mrs. Virginia Robinson

Mrs. Virginia Robinson

In Dallas, Martha Simkins became quickly recognized as an accomplished portrait painter and received regular commissions from prominent local citizens. Several artists seemed to have had a possible influence on her style. In addition to Chase, it appears that her early training with Kenyon Cox played a role in her development as an artist since he specialized in teaching life, anatomy and antique classes at the League for more than twenty years and she was enrolled in these classes when she first arrived from Dallas. She also studied with Mowbray, a realist who executed orientalist elements, and this can be seem in several of her flower still lifes. The teacher with whom she probably studied for the longest period was Frank Vincent DuMond who taught at the League for more than fifty years. DuMond was thought of as an inspiring and committed teacher and though League records are incomplete, Simkins was definitely enrolled in classes with him during 1914-1916, 1918-1919 and 1921-1922, taking mostly portrait classes, as well as at least one life class.

In addition to her known instructors, several artists of the period may have had strong impact on her development. An anecdote places her in contact with John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), both of whose somewhat impressionistic images and choice of portraiture as primary subject matter may have been the inspiration for her own style and specialization. She told her good friend, Roger Saunders, that she had been taught by them, although no documented materials connected to them have been located and neither artist is known to have taken on students. Simkins has also been connected with Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) and Emil Carlsen (1856-1932) and while their possible influence can be seen in certain composition, there is no documentation to specifically link her to them. Some of her still lifes have a refinement similar to that of Carlsen, who was a skillful and highly regarded painter and specialized in that genre, and Simkins surely was familiar with his work from public exhibitions. As for Beaux, who specialized in rich painterly brush work, she taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and no records have been located too prove that Simkins ever attended the school. In discussions with Roger Saunders, Simkins recalled that Beaux had critiqued her work and refers to taking notes from Beaux; and it may be inferred that she heard her give a lecture, although we have no exact date. As for Carlsen, he moved East in 1891 and taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and at the National Academy of Design's school. Again, Simkins is not known to have attended either school, but the similarity in technique in her still lifes seems to have been influenced by him.

Young Girl in Middy Blouse

Young Girl in Middy Blouse

Beside Chase, another artist who appears to have had a great impact on Simkins' development is Robert Henri. The direct style of portrait painting that she employed reflects a philosophical outlook similar to Henri's and he clearly exerted influence on her. Interestingly, although his influence is apparent, and he was known at the League as an extremely charismatic and inspiring teacher, she never mentioned him in any correspondence or in discussions with Roger Saunders. Henri taught at the League from 1915-1927 and this overlapped with several of her sessions there. In the late 20's, Henri was an extremely well-known portrait painter, author, frequent exhibitor, and influential teacher. Several portraits in the exhibition clearly reflect Henri's influence including Lady in Red Dress (c. 1925), The Spanish Girl (c. 1925) and some of her likenesses of children, Bobby (c. 1910), and Girl in Middy Blouse (c. 1910). Another artist that may have influenced Simkins was Irving Wiles (1861-1948). Wiles was a protégé of Chase. Through her friendship with Gladys Wiles, daughter of the artist, Simkins spent some time in the Adirondacks with the family during which time it is thought that Wiles may have offered her encouragement and advice. Wiles excelled at portraiture although he painted interior scenes, seascapes and still lifes and Simkins was certainly familiar with his work and style.

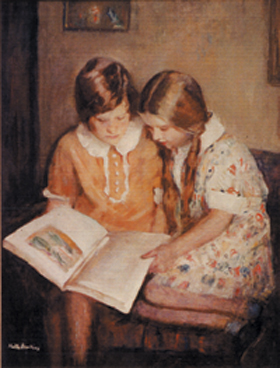

Two Girls Reading

Two Girls Reading

In addition to Simkins' interest in portraits which were commissioned by prominent Dallas citizens, portraits of children, several self-portraits, the first of which is dated about 1910 when the artist was in her mid-forties, Simkins extended her interest to include figurative compositions in interior settings. One of the earliest of this genre is Girl Crocheting (c. 1910), which, according to the artist's recollection, was done at the summer session of the Art Students League in Woodstock. The school had opened in 1906 and with the passage of time, became America's best-known summer artists' colony. The painting harks back to Dutch interior scenes of women engrossed in needlework, and there is a similar atmospheric stillness and realism. The pensive downward gaze of the young girl also contributes to the contemplative mood of the composition, one that is evocative of the works by Vermeer. Simkins has engaged spatial depth by showing a door opening off into another room with a chair in the distance, although no other figures are present. Simkins often incorporated the strategies used in these interior genre scenes in several of her portrait commissions, including Two Girls Reading (c. 1930), and a more traditional depiction of a mother and daughter done over twenty-five years later, Anne Davis Hall and her Mother (c. 1951). The former painting is a typical impressionist subject depicting two young girls engaged in looking at a book while sitting together on a sofa. Like, Girl Crocheting, a sense of tranquil calm pervades the scene, although Simkins later related that "These two girls look so angelic, but they were hellions to paint, because they would not sit still for long." In this work, the artist employed highly keyed tonalities, painting the young girls in brightly colored clothing. In the portrait, Anne Davis Hall and her Mother, the artist again used lighter contrasting attire to highlight the subjects. The exhibition includes a detailed preliminary pencil sketch of this work and a photograph used for the sketch, thus, illustrating Simkins' use of photography in the execution of some of her commissioned compositions.

Still Life with Copper Pot

Still Life with Copper Pot

Simkins had a real facility for still life painting, at least equal to that of portraiture, and this has resulted in a significant body of works in that genre. Some of her still lifes display an exceptional aesthetic refinement, and in the floral subjects, which she favored, she tends to focus on the beauty of each individual blossom. Roses were a favorite subject and inspired her earliest known still life piece, Pink Roses with Chinese Jar (c. 1900), although she painted magnolias, chrysanthemums, daisies and other varieties. The composition is structured and undertaken in much the same manner as her portraits, with a dark background and light that accentuates the blooms, the focal point of the composition. Her predilection for roses can partly be explained by the fact that her neighbors often brought her roses and she is able to convey in the handling and technique a contrast of textures of the petals and that of the vessels. Simkins most often opts to paint the blooms in a casual, unstructured arrangement. This approach recalls the work of other noted American still life artists, Emil Carlsen, George Lambdin, J. Alden Weir, Chase, and Abbott Thayer. Simkins' consummate painting, Roses (c. 1935), depicts some white blossoms in a glass positioned against a gray background. The contrast offered by the green leaves and the shadows highlights the artist's handling of the blooms and the reflection of the glass. Such techniques, necessary to render flowers and reflective surfaces, have traditionally been tests of the accomplishment of a still life painter and in this she excels. It is extremely curious that Simkins did not emphasize her abilities as a still life painter in public art exhibitions and current research indicates that only one still life painting (an untitled composition) was exhibited at the 1927 National Academy of Design annual exhibition. Simkins' most elaborate composition and possibly her most accomplished still life is Still Life with Copper Pot (c. 1920). The grand dimensions of the painting which presented intricately arranged objects including grapes, a vase with flowers, a copper teapot, and a large brass plate, are situated on a tapestry-like surface. By presenting such a variety of objects and textures in such a complex arrangement, it would appear that she was attempting to demonstrate her skill as a still life painter. Though we have located no exhibition record of this work, the painting, because of its scale, intricacy and finish, appears to have been an exhibition piece, though it can be said that still life painting for Simkins generally seems to have been a more private means of self-expression for her than her commissioned works.

Simkins continued to exhibit in the State of Texas when she permanently moved back in 1934. She exhibited at the Fort Worth Annual Exhibitions of Selected Paintings by Texas Artists in 1926-1928, 1930, 1936, and her paintings were included in two exhibitions of Texas art that traveled throughout the state, including Houston in 1931 and Dallas in 1941, respectively. She exhibited the work The Spanish Girl in the Texas Fine Arts Exhibition's Work of Texas Artists in 1932 and she also entered a portrait (title and current location unknown) in the Texas Centennial Exposition's exhibition of art held at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts in 1936. Among the 600 works of American and European artists, were 164 by Texas artists, thus making this one of the largest presentation of Texas art that had ever been made available to the public. Simkins exhibited in several exhibitions that solely featured the work of women artists and she seems to have embraced, to some degree, her identity as a "woman artist". One question raised by this exhibition is whether her association and exhibiting her paintings with other women artists of her generation tended to limit or pigeonhole her reputation as a "female artist". Woman patrons, female sponsored organizations, and an extremely large community of women artists including Simkins, were integral to the development of art in Dallas and in the State of Texas. It appears that women led the way in organizing major art exhibitions under the auspices of such regional and local groups as the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs, the Dallas Art League, the Junior League, the Houston Public School Art League, and the Dallas Woman's Forum. Additionally, major local museums, including the then Fort Worth Library of Art Gallery (now the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth) were essentially established by female patrons. Although her reputation was sometimes limited or shaped by her gender and by her extreme popularity with local and regional women's groups, Simkins did establish herself as a highly regarded painter and she was shown along with the other major regional painters of the day although she did not receive the recognition that was accorded to male painters. In 1926, the Dallas Morning News wrote that Simkins "has brought much distinction to the city . . . because of the high praise she received as one of America's leading woman portrait painters". In A History of Texas Artists and Sculptors (1928) the author, Frances Fisk, noted that "Simkins is one of America's most distinguished painters . . . [she] has brought much honor to Dallas and her progress as a portrait painter is well worth watching." Early in her career, she came to the attention of the most important art gallery in Dallas at the beginning of the twentieth century, Joseph Sartor Galleries,, and they regularly displayed her work. She was featured in numerous exhibitions at the gallery for almost 30 years, and her last exhibition was as part of the Klepper Club Exhibition in 1951.

Because of the illness of her mother and family obligations, Simkins remained in Dallas, painting almost up until her death at the advanced age of 103. It is impossible to know what position Simkins would have occupied on the national scene had she chosen to remain in New York City and pursue her career more vigorously in a more widespread public arena. One of the leading questions for future scholarship is while she remained highly active painting and teaching in Dallas, it remains a mystery why she removed herself from exhibiting her paintings in national venues after she moved home. Judging from the success of the work Portrait of Mrs. C, and given that her life as a painter was remarkably long, it will never be known what she might have accomplished had she been free to choose a difference course, unencumbered by family responsibilities that frequently fell to unmarried women of her time. Her career is distinguished for its length, her commitment to art, the body of work that has been discovered to date, and her quest for artistic growth, exemplified by her attendance at classes at the Art Students League even into her mid-nineties. For an artist who in 1926 was said to have "achieved enviable fame as a portrait painter", it seems improbable that she would have come to such obscurity, though it is not unusual in the art world. It is only through the legacy of her surviving work, some of which is shown in this traveling exhibition, and the dedication of her custodians and patrons, both past and present, who have taken on the mantel of bringing to light her oeuvre and resurrecting her reputation, that Martha Simkins regains a measure of public attention.

Note: The foregoing is excerpted from the essay Martha Simkins: An Introduction to her Life and Work, by Dr. Valerie Leeds and the essay Martha Simkins: Cultivating a Regional Reputation by Dr. Melina Kervandjian in the exhibition catalogue.

See related

article in the September 2002 issue.

Mailing Address: Carolina Arts, P.O. Drawer

427, Bonneau, SC 29431

Telephone, Answering Machine and FAX: 843/825-3408

E-Mail: info@carolinaarts.com

Subscriptions are available for $18 a year.

Carolina Arts

is published monthly by Shoestring

Publishing Company, a subsidiary of PSMG, Inc.

Copyright© 2002 by PSMG, Inc., which published Charleston

Arts from July 1987 - Dec. 1994 and South Carolina Arts

from Jan. 1995 - Dec. 1996. It also publishes Carolina Arts

Online, Copyright© 2002 by PSMG, Inc. All rights reserved

by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. Reproduction or use

without written permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina

Arts is available throughout North & South Carolina.