The Photographs of 0. Winston Link

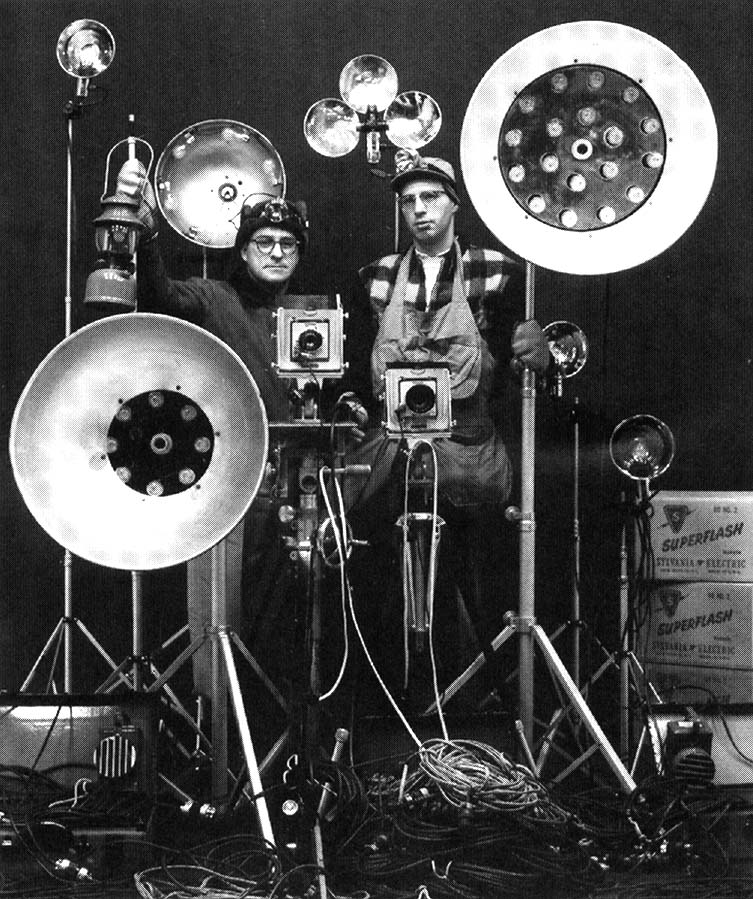

Winston Link was a young practitioner of an old photographic tradition, one still much used, hut which now commands little public notice. He developed a strong personal style within the technique of using cameras that were usually fixed in place, mounted on heavy tripods and using large negatives, typically 4 x 5 inches in size. The dynamic qualities of photographs made this way came through their careful planning: the precise placement of the camera, and equally careful placement of the lighting sources, with people and objects also being arranged with an eye for the final effect. Photographs using this technique were (and still are) made by the millions for advertising and illustrative purposes.

While this manner of photography is still widely used, we have come more often to think of photographic "truth" through another aesthetic, one created by photographers using small hand held cameras. Sometimes described by the generic term "street photography" photographers who work in this way usually move rapidly and invisibly through their surroundings, making images using only the light available and leaving the environment untouched and unchanged.

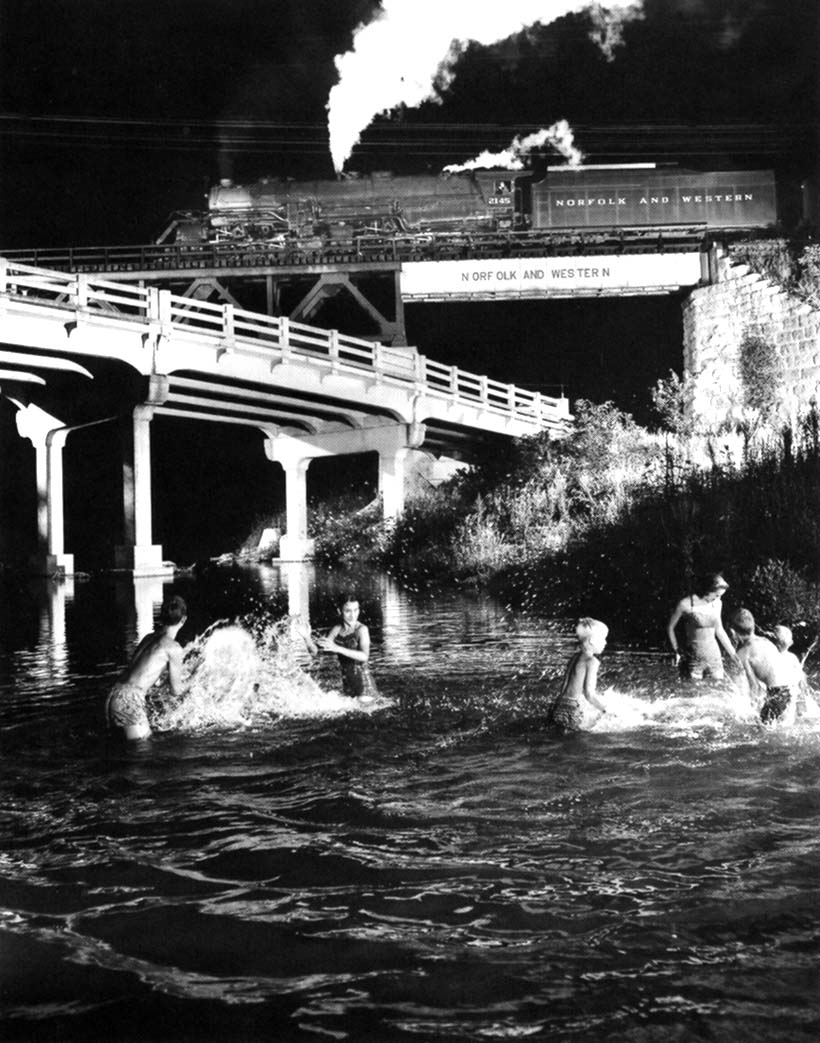

Not only did Winston Link use a different photographic technique, his motivations were different from street photographers His interest, in all his work, was to create as precise and careful a record as possible of the scene being photographed. Using lessons he learned from his commercial advertising photography, Link had less interest in documenting life as he found it than in creating images of life as he (or his clients) might wish it to be. Thus in his railroad photos, Link built a record that not only documented the locomotives and trains themselves, but emphasized the benefits of the railroad to the life of the communities through which it passed. He was, in his way, preparing and executing an advertising campaign for the "American Steam Railroad," and the good life in the United States which it supported. In many of his photographs the passing train is incidental to the activity in the foreground, be it buying groceries, taking a swim or herding cows. Yet, even in the background, the steam railroad was still the essential element which stitched together Winston Link's personal vision of this good life in America.

O. Winston Link and History

One lesson Winston Link learned from his father was how to tell a good story. His skills at weaving a tale were transposed into his photographic vision as well. He was able to see an image in his mind that would exist in reality only for the split second it took for the flashbulbs to ignite and record the event on film. He often worked in all but perfect blackness, on occasion spending days to make a single photo all for the benefit of adding a page or chapter to his story of this steam railroad.

While he loved railroads, Link never considered himself to be a "railfan." He didn't travel around the country to visit railroads, nor was he interested in making static photos of as many steam engines as he could find. When he was shown such photos, he dismissed them as "hardware shots," because the locomotives were no longer in their normal environment of their life on the tracks or along the line.

Like a good story teller Link was also willing to wait until his audience was ready for the tale. He made little effort to have his railroad work seen, beyond publication of a few photos reproduced in railroad magazines, until the mid 1970s, and it was not until 1983, almost thirty years after he started the project, that these photographs received their first museum exhibition. Since that time they have been widely exhibited and published, and many people who otherwise would have no interest in photographs of railroads have warmly responded to them. The reason for their wide appeal must lie in the breadth of the project's conception, and in the care taken in its execution. These photographs are period pieces, bits of another time and place, but they are also images created with deep respect for the people photographed, the places where they lived and worked, and the splendid machines they operated.

O. Winston Link

Winston Link was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1914, the son of a school teacher. Early on, Link showed an aptitude for technology, and his father, a demanding man but a good instructor introduced him to a variety of options. The elder Link trained his son to handle tools well and encouraged his interest in photography. It was at this time that he also developed an interest in steam railroading which was to remain with him for life. Link attended the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, where he was a good student and a popular one, being particularly well known for his practical jokes. He graduated in 1937 with a degree in civil engineering, but photography was to claim him before engineering could.

Engineering jobs were scarce in Depression America, but Link was offered a position as photographer for a large public relations firm. His job was to make photos for his clients which were submitted for free use in newspapers and magazines. The photos had to carry the clients' messages, and do it with such cleverness and wit, or be so unusual, that photo editors couldn't resist using them. In this job he learned to use people to animate his pictures, and how to give them both compositional "punch" and the vivacity editors wanted.

With the onset of World War II, Link used both

his engineering and photographic skills as a photographer and

researcher for a secret military project, designing and building

devices to detect submerged enemy submarines from airplanes flying

overhead. The research laboratory was located in Long Island,

adjacent to the tracks of the Long Island Rail Road which was

powered by steam at that port. Link renewed an interest in steam

locomotives and railroads that had been all but dormant for some

years, and began to photograph them.

In 1946, with the end of the war, he chose to become an independent, free lance photographer and opened his own photographic studio, first in Brooklyn and later in Manhattan. His clients included many major American companies and leading advertising agencies who called him when they needed a photographer with a knowledge of large cameras and complex lighting setups. It was during this, from January, 1955 to March, 1960, that he created the documentation of the last years of steam railroading on the Norfolk & Western Railway. He retired from active practice in 1983, and now lives in Westchester County, New York.

Winston Link's photographs of the Norfolk & Western Railway are documented in two books, Steam, Steel and Stars, 1987, with text by Tim Hensley, and The Last Steam Railroad in America, 1995, with text by Thomas H. Carver. Both are published by Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York, and both are in print.

O. Winston Link and the Norfolk and Western Railway

Winston Link has loved railroads for just about as long as he can remember. As a teenager, he and his friends would take the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan and cross the Hudson on a ferry to spend the day in the Jersey Central or Baltimore & Ohio railyards in New Jersey. He photographed the railroads then, and continued to do so during the early part of his professional photographic career, but just for pleasure. Gradually, however, Link realized that the steam locomotive was disappearing, and with it a network of railroad towns and repair shops which it supported. Also disappearing was a quality of life that he saw as a personalized relationship between the railroads, their employees and the powerful but very labor intensive steam locomotives. The desire to preserve a record of this time and these places was the basis of the motivation that gave him the energy to create a visual document of a whole manner of life that was fast disappearing. It was a massive private undertaking, financed entirely by the photographer, that resulted in the creation of a five year long cycle of photos of the last years of steam railroading on the Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W) in Virginia, West Virginia and North Carolina.

By 1955,the N&W was the last major American railroad to operate exclusively with steam power. The N&W (since merged with the Virginian Railroad and the Southern Railroad and now known as Norfolk Southern) was one of the country's major coal haulers, moving coal from the mines in West Virginia east to Norfolk, Virginia, for ocean shipment up and down the coast and overseas, and west to users in the Midwest. The railroad was true to its major customers, but the steam locomotive is a hugely labor intensive machine, and despite the cheap fuel available, parts were becoming scarce and by the mid-1950s it was clear that its days were numbered.

Early in 1955 Winston Link was sent to Virginia on assignment, and he took the opportunity to watch N&W steam trains at Waynesboro, nearby. After one night of watching, he activated an idea which had been a fantasy in his mind for more than a decade. He would photograph the railroad at night, using flashbulbs synchronized to the camera's shutter. This way he would be able to stop or slow the motion of the train, while being able to control the light on his subject, just as a cinematographer controls light, to emphasize certain areas while making distracting elements disappear. He went hack to Waynesboro the next night, January 21, and tried his ideas by photographing an arriving passenger train. They worked perfectly.

Link approached the management of the N&W with a proposal. He asked for no compensation, but wanted permission to enter onto railroad property to make photos. The president of the N&W at the time, R. B. Smith, had been with the railroad more than 40 years and loved his steam locomotives. The N&W responded positively and in March, 1955, Winston Link made the first of at least 20 trips to the N&W to begin the project which continued until March, 1960, just a few weeks before the N&W terminated all steam operations. He financed the entire five year cycle of photographs from the profits of his successful photographic practice, and recovered almost none of his expenses until his work began to be exhibited and collected in the early 1980s.

Link began his task by spending the first year photographing along the railroad's right of way or in its shops and yards. He worked mostly at night, but photographed in daylight as well, primarily along the railroad's mountainous Abingdon Branch, a 55 mile spur that ran one train a day, six days a week, from Abingdon, Virginia to West Jefferson, North Carolina. He perfected his flash equipment during this time and in its final form this flash power supply could fire 60 flash bulbs synchronized to the shutters of up to three cameras in an instantaneous blaze of light equal to 50,000 watts of illumination. He also spent days traveling on the railroad's passenger trains, watching for possible photo sites from each side of the train. Maps and suggestions from railroad men also provided leads for good spots to photograph.

As he came to know the railroad, its often rugged environment and the colorful people who worked for the road or lived along it, Link expanded his vision. In many of the photos he made beginning in 1956, the trains became the background to the life lived along the tracks. Whether chatting quietly, pumping gas or going to the drive-in, the train was always there. He also returned to the Abingdon Branch that year to create some of his most memorable photos made during daylight hours.

By 1957, steam had been removed from several

divisions of the railroad, and Link concentrated on recording

the splendid J class streamlined passenger engines before they

were withdrawn from service on most runs. By 1958 steam was regularly

found only in the western end of the N&W, working in the coal

fields of West Virginia. By 1959 there was not much steam left,

and Winston Link again concentrated on the engines themselves,

so soon to be gone, but this time photographing them in a more

expressionistic way, trying to record in static images some sense

of that incredible surge of flailing, ground shaking energy as

these engines, some weighing upwards of one million pounds, thundered

past in the dark.

Mailing Address: Carolina Arts, P.O. Drawer

427, Bonneau, SC 29431

Telephone and Answering Machine: 843/825-3408

E-Mail: carolinart@aol.com

Carolina Arts is published monthly by Shoestring Publishing Company, a subsidiary of PSMG, Inc. Copyright© 2008 by PSMG, Inc., which published Charleston Arts from July 1987 - Dec. 1994 and South Carolina Arts from Jan. 1995 - Dec. 1996. It also publishes Carolina Arts Online, Copyright© 2008 by PSMG, Inc. All rights reserved by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. Reproduction or use without written permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina Arts is available throughout North & South Carolina.